Export Products from the Curacao Plantations

(Published in the newspaper Amigoe on the 18st of June 2025)

Most plantations produced for their own use or supplied products to the city. But some plantations took it a step further and exported some products. However, this wasn’t an easy feat. Check out the article below for more details!

EXPORTS

Curaçao’s agricultural exports have never really taken off. But there were a few times when plantations did pretty well. That happened when world prices for their products were high. But in the long run, things didn’t work out so well. There weren’t enough buyers, prices were low, there was a drought, and there were diseases. So, the export of plantation products never really caught on.

Governor Van Raders (1836 – 1845) was one of the few who really wanted to export plantation products. In 1837, the government rented the plantation Plantersrust and bought it in 1839. They set it up as a model plantation to test different crops like Cochineal and Aloe that they wanted to export. Van Raders also stimulated salt extraction. But not everyone in the city liked his ideas. Curaçao was mostly known for trading, and people thought the island wasn’t very good for farming because of the low rainfall.

While plantation export products didn’t do so well, it’s still worth looking into from a historical and cultural perspective, especially since it had a big impact on the landscape. Here are a few examples of plantation export products.

Salt

Curaçao was taken over by the West India Company (WIC) from the Spanish in 1634. The WIC was a privateering company that needed a naval base. But they also wanted a good source of salt for herring gutting, among other things. In herring gutting, the intestines and gills of the herring are removed right after catching them. Then, the herring is put in super salty water. The herring doesn’t spoil. The salt was made in salt pans on Curaçao by the WIC and later by private plantations. To do this, they built low walls in part of a bay. This divided part of the bay into compartments. Then, they closed off the compartments for salt extraction. The water evaporated, and the salt was left behind. In the bay of Rif St. Marie, for example, were the salt pans of the plantations Hermanus, Siberie, Jan Kok, and Rif St. Marie. The enslaved people scraped up the salt and put it in bags. Working in the salt pans was super hard work because of the heat. The sunlight reflecting off the white salt also caused eye problems. The bags of salt were collected by ships (see the attached photo). This made salt Curaçao’s first export product.

Shipping of salt from Santa Martha (1903)

Photo Credits: Soublette

Brazil Wood

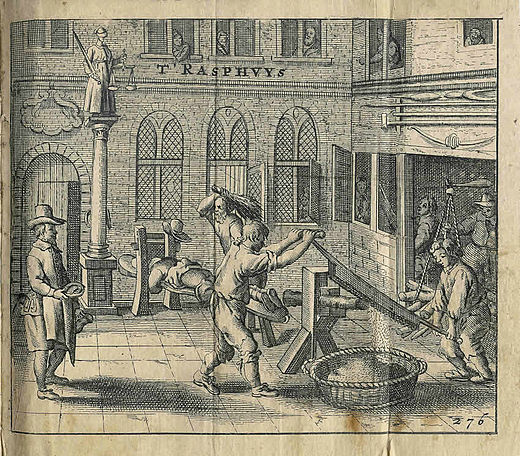

Brazil wood mainly came from Brazil, which also derives its name from it. You know, Brazil wood was also popular on Curaçao back in the day. The Spanish started cutting down brasil trees way back when. This wood can be used to make a red dye. People used it to color textiles, among other things. Before you could use it, you had to grind it up. In the past, they did this in Amsterdam by male prisoners in a place called the “rasphuis.” The big-time cutting down of brasil trees on Curaçao has hurt nature because of all the deforestation.

The Rasphuis from "Beschrijvinge der wijdtvermaarde Koopstadt Amstelredam" (Melchior Fokkens)

The wood of the Wayaca tree

The Wayaca (Guaiacum officinale) was also cut down. The wood of the wayaca tree is also called “pokhout” in Dutch. In the past, an extract of the wood was used as a medicine against Spanish smallpox (syphilis). This wood is super heavy and tough, but it sinks in water because of its weight. In the past, people used it to make pulleys and propeller shafts for small ships at home and abroad. It’s so greasy that the pulleys and propeller shafts didn’t need any lubrication. Now, all Guaiac species are on the CITES II list, so you can only export them with a permit. Cutting down wayaka trees has also led to deforestation.

Dividivi

The dividivi pods come from the Watapana (Caesalpinia coriaria) tree. That’s why the tree is also called Dividivi. It has a unique growth pattern with the wind. When the dividivi pods are ripe, they contain tannic acid, which was used for tanning hides. In Europe, oak bark was the main tanning material. When oak bark was scarce, dividivi pods were exported to Europe as a substitute. People would pick up the pods lying on the ground to harvest them. On plantations, dividivi trees were treated with care. However, on public lands, there was less control, and sometimes, unripe pods were beaten out of the trees with sticks. In some cases, entire trees were even cut down to get the pods. Unripe pods were sometimes buried in the ground to turn brown and be sold as ripe pods. This didn’t improve the quality or reputation of the product. Dividivi trees were also used to make charcoal.

Indigo

Indigo is a blue dye made from the Indigo plant (Indigofera tinctoria). People used it to color textiles. Indigo was grown on many plantations. They used special tanks called “indigo tanks” (bak’i blous in Papiamento) to extract the blue dye from the indigo plants. These tanks needed a lot of water, so they were always near small streams or wells. An indigo tank is like a row of three tanks, with the top one filled with water. The indigo plants were put in the top tank and weighed down with blocks of wood. They let the plants ferment in the water. The blue water was then moved to the second lower tank, where it was stirred. The indigo globules sank to the bottom. They did this again in the third tank. The sediment was scooped out of the container, dried, and then sold. In Curaçao culture, indigo dye (blous) is also used to protect against evil spirits. It’s still sold in boticas, but now it’s a chemical version.

Indigo tanks near Zevenbergen (two systems)

Photo: Paul Stokkermans

Cochineal

Cochineal is a red dye made from tiny insects called cochineal lice. These lice live on the needleless Nopal cactus, which is native to Mexico. In Dutch, a field of nopal cacti was called a “nopalerie.” But producing cochineal was tricky. It took three years for a nopalerie to yield a profit, and it was often hit by droughts and diseases. When synthetic dyes became available, the demand for cochineal dropped. Savonet was one of the first companies to start growing nopal cacti for dye production. Mathias van der Dijs, the owner of Savonet, built a nopalerie in 1836.

Aloe

Aloe cultivation is not difficult because aloe plants do well in Curaçao. The process of making aloe resin for export was straightforward. They cut off the aloe leaves and put them in drip trays. The juice collected at the end of the drip tray was then boiled in copper kettles. The thickened juice was poured into gourds or boxes, where it solidified into aloe resin. But exporting aloe resin wasn’t always a hit. There wasn’t always a big demand for it internationally, so the prices were low, except for a few good years.

Aloe drip trays (1930)

Photo Credits: P. Wagenaar Hummelinck

Current potential plantation export products

Can something be done with this interesting past in the present time? Guess what? Aloe Vera Farm is back in the export game! They’ve got a whole bunch of cool products now. Maybe we should give the other export products mentioned in this article some more attention in museums or even set up demonstration projects for locals and tourists.

In the next article, we’ll dive into the world of Sorghum (maishi chikí) cultivation on the plantations. Sorghum was the most important crop, and it was used to make funchi. Funchi was a staple food for the enslaved people on the plantations.

9. Export Products from the Curacao Plantations