The Paga Tera System

(Published in the newspaper Amigoe on the 30st of July 2025)

In the last article, we talked about the big picture of the Curaçao plantation - its economic importance, how profitable it was, and how it was financed. Now, let’s shift our focus to the ‘paga tera’ system that came into play after slavery ended in 1863.

The abolition of slavery in 1863

Slavery in Curaçao was abolished in 1863. The Netherlands was late in this. In the English colonies in the Caribbean, slavery was already abolished in the period 1834 – 1838. In the French and Danish colonies, slavery was abolished in 1848. The abolition of slavery obviously had consequences for the plantations.

Occupation of public lands by ex-enslaved persons before 1863

After the plantations were set up, the less fertile areas remained. These public lands were also called savannas, and they belonged to the government. The owners of the plantations used these public lands to graze their cattle. Sometimes, they even got permission from the government to do this. But the owners of the plantations thought they had the right to graze on the public lands, even though that wasn’t actually the case. In some cases, they even thought they owned certain public lands!

Before the abolition of slavery, the so-called "free people" already lived on the public lands. These were mostly former enslaved people who had obtained their freedom. They often lived in scattered houses, often with a piece of land, on which sorghum (maishi chikí) was grown. The owners of the plantations often turned a blind eye to this on the condition that only the sorghum panicles were harvested. The sorghum plants had to be left standing. The owner of the plantation then had the sorghum plants eaten by his cattle. This was of course illegal because the public lands were owned by the government and not by the plantations. The freemen on the public lands were often not allowed to keep goats because, according to the plantation owner, they could damage the crops on the plantation. Donkeys were often only allowed insofar as they were needed for their own transport. If the plantation owner did not like the residence of a free person on the public grounds, he had him removed. The government usually sided with the plantation owners in case of complaints.

The position of the ex-enslaved persons after 1863

In 1863, slavery ended, and the number of free folks skyrocketed. But guess what? The plantations still needed workers. The planters weren’t too keen on the ex-slaves owning their own land. You see, they were worried about losing their hardworking labourers. So, they came up with the so-called “paga-tera” agreement, which basically tied the ex-slaves to the plantation.

Paga tera means "to pay for land". The former slave was allowed to stay on the plantation in his small hut as a tenant. He could grow his own sorghum and other crops. This plot was called the “kunuku.” Kunuku is an Indian concept that’s been enriched with African crops and customs. He could also make charcoal. He could also keep small animals like goats, pigs, and chickens. He could also keep a few donkeys.

In exchange, the sorghum stalks were for the owner of the plantation. He used the sorghum stalks as cattle feed. The ex-enslaved person also had to work for the planter for 12 days without pay, but in exchange for the provision of food. In addition, the ex-enslaved person was obliged to work on an on-call basis for the planter as soon as he needed them. Ex-enslaved people could be further removed from the plantation as soon as they were brutal or lazy in the eyes of the planter.

From a business perspective, this system was advantageous for the plantation owner. He’d already gotten paid by the government for losing the enslaved people. Now, he didn’t have to worry about taking care of the non-productive enslaved people like kids, the old folks, and the disabled. The ex-enslaved folks often had no other choice but to accept the paga-tera agreement. Outside the plantation, jobs were scarce. So, the plantation owner could keep his old power position. During long, dry periods when the harvest failed, the ex-enslaved folks were sometimes forced to work abroad temporarily. The government mostly looked out for the planters’ interests. In 1879, a government decree was made that people living on the public lands couldn’t keep more than five goats and two donkeys. This was to stop people from living on the public grounds.

Around 1885, this unjust situation for ex-enslaved people changed due to the actions of the then district master Eskildsen. When the government leased pieces of land to ex-enslaved people based on his advice, more than 50 plantation owners objected to this. In various memorandums, however, Eskildsen brushed off the planters' arguments.

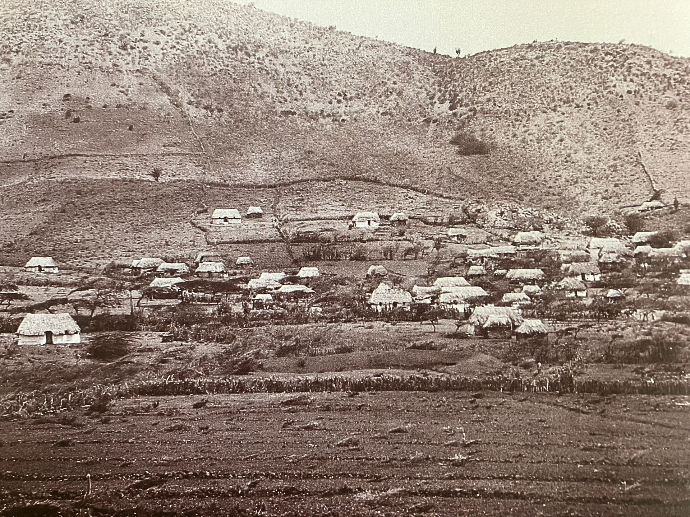

Habitation of Westpunt on government land 1900 – 1904 (Foto Soublette)

In the first decade of the twentieth century, during the reign of Governor De Jong van Beek en Donk, plantations were bought up and divided into pieces of two hectares and leased to candidates. However, the living conditions of those who continued to live on the plantations changed little.

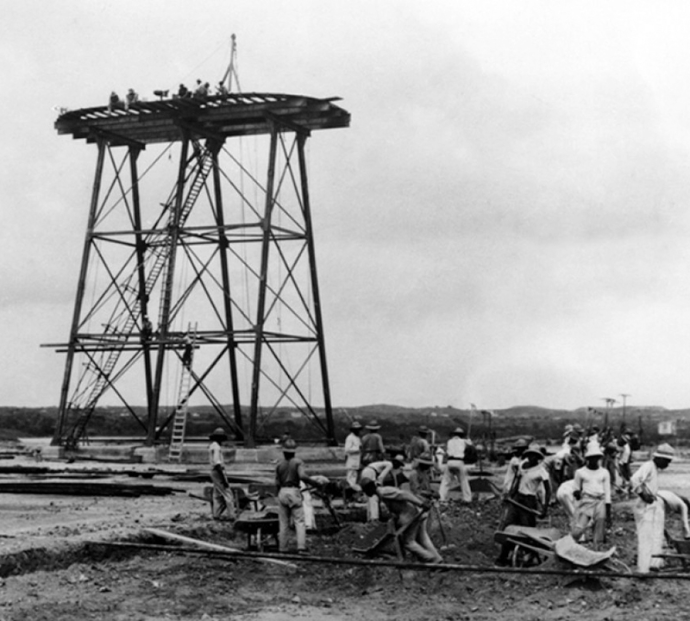

In 1915, Shell made its mark in Curaçao. Shell built an oil refinery right at the Schottegat. Curaçao was close to the oil fields in Venezuela near Lake Maracaibo. The natural harbor in the Schottegat was perfect for big ships. The refinery became one of the biggest employers on the island and was a key part of the island’s economy for the whole 20th century. That’s when the plantations finally lost their top spot. Lots of workers left the plantations and went to work at the refinery. That was the beginning of the end of the plantation era.

Establishment of Shell in Curaçao

Summary of the plantation series

In this article, the paga tera system has been discussed. This is the final article in this series. The plantations were established after the WIC took control of Curaçao. We’ve explored how waterworks were constructed on the plantations to ensure a steady supply of water. We also delved into the construction methods, materials used, and architectural features of the country houses. It turns out that plantations weren’t just for local consumption on the plantation and sales in the city; they even managed to export products on a small scale. We went into great detail about the cultivation of Sorghum (maishi chikí), which was crucial for food security. Additionally, we examined the role of the (company) plantations in establishing the maritime support center of the WIC, their involvement in the slave trade, and their profitability. This last article discussed the situation after the abolition of slavery. How the plantation owners have tried to actually maintain slavery in a different form through the paga-tera system. And how this came to an end with the arrival of the Shell.

In the end, it was not the colonial government that put an end to the pseudo-slavery of the paga-tera system, but the new economic opportunities that the refinery offered. The alternative employment at the Isla in the early twentieth century led to major shortages of workers on most plantations, which also brought the plantation era to an end.

12. The Paga Tera System