The Cultivation of Maishi Chikí (Sorghum) on the Curacao Plantation

(Published in the newspaper Amigoe on the 1st of July 2025)

In the last part, we talked about the export products on the plantation. Now, let’s dive into the main crop. It’s called “maishi chikí” in Papiamento.

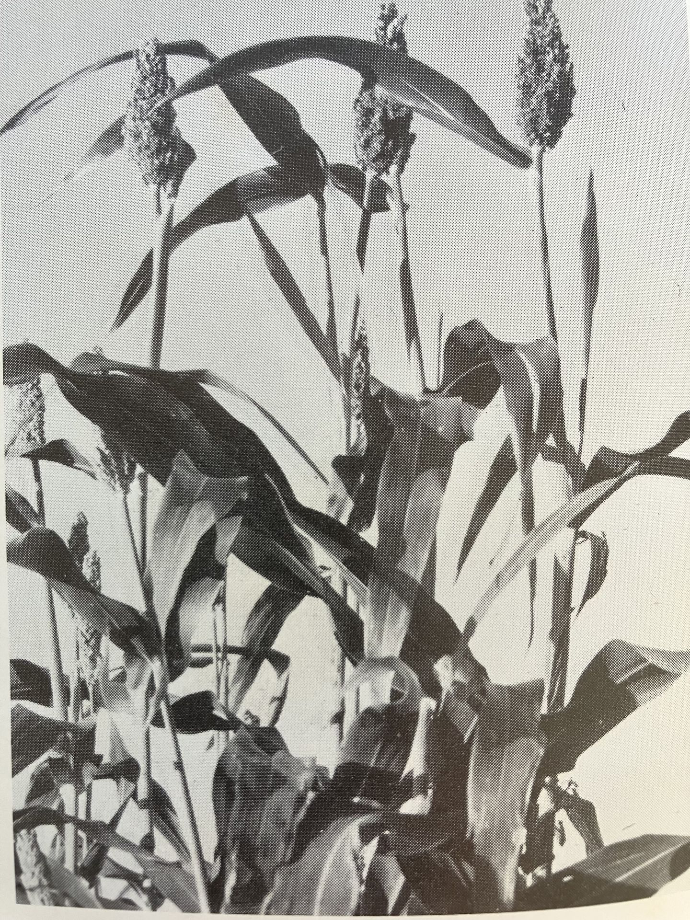

Sorghum (maishi chikí)

Photo credits: Cultivated and useful plants of the Netherlands Antilles (Fr. M. Arnoldo)

Funchi

The plantations were run by enslaved people, but they still had to be fed. The main food was funchi, which was made from the seeds of the sorghum plant. Sorghum is a tough plant that can grow in dry conditions and is packed with vitamins and minerals. It’s also high in fiber, protein, and antioxidants, and it’s gluten-free. The starch in sorghum digests slowly, which helps keep blood sugar levels steady. In general, sorghum is even healthier than corn. But sadly, funchi is often made with corn flour these days.

Sorghum, the main crop on a plantation

Sorghum is a super important food crop worldwide. In Papiamento, it’s known as “maishi chikí” or “small corn.” Can you guess why? The sorghum plant looks a lot like the corn plant called “maishi grandi” in Curaçao. The only difference is in the flowers. Corn has big cobs with pretty big seeds growing in the axils of the leaves. But sorghum has a panicle (called “tapushi” in Papiamento) on top of the plant. And guess what? Sorghum seeds are smaller than corn seeds. That’s why it’s called “small corn.”

Tapushi maishi chikí

Photo credits: Prins Doran (Dokterstuin)

Sorghum is a great choice for Curaçao’s hot and dry climate. It’s more drought-resistant than corn and can grow in poorer soils, needing less fertilizer. There are different types of sorghum, and Curaçao has its own special kind. That’s because Curaçao is an island, so it’s all by itself and can develop its own unique traits.

Water requirements of sorghum

On Curaçao, you could grow fruits and veggies, and even raise cattle, on plantations with wells. But the wells weren’t enough to water the sorghum fields. So, sorghum farmers had to rely on the rain. The rainy season on Curaçao is from October to January. That’s when sorghum farmers planted their fields. They usually sowed the sorghum in September, just before the rainy season, or in October when the first rain came.

Sorghum needs about 300 to 400 millimeters of rain to grow. Curaçao gets an average of 550 millimeters of rain each year, so it should be enough. But sometimes, the harvest fails because there isn’t enough rain. Here are some reasons why:

- The rain had to fall in the months of October – January. Rainfall outside this period does not count.

- In the period October – January, the rain should fall in a staggered manner. Everything in one month is harmful.

- The rain must fall on the field where the sorghum is grown. On Curaçao, the rainfall is often local. On one plantation it could rain, and people had a good harvest, while on another plantation there was less or no rain, resulting in a failed harvest.

If these conditions weren’t met, the chances of a failed harvest were super high. That meant the plantation owner had to buy food to feed the slaves. Famine could strike Curaçao hard if there were a few dry years in a row and the harvest failed.

The cultivation of Sorghum after the abolition of slavery

Echi Cijntje, author, and a local from Savonet, recalls the sorghum cultivation he witnessed during his childhood. He mentions two main types of sorghum: the “pichipé” and the “karabama”. The pichipé had panicles that formed in a more compact way, while the karabama had panicles that were loosely separated. The pichipé was the most popular variety. Every September, people would plant sorghum seeds to wait for the rainy season. Others would wait for the first rain to plant their seeds directly in the ground.

Sowing was done by making rows of holes in the ground. A few sorghum seeds were placed in each hole, and sometimes bean seeds (bonchi) were also added. The corn stalks usually grew between 1.80 and 2.00 meters high. Since you had more seeds per hole, you often saw several sorghum stalks together. The bonchi of Curaçao is a climbing plant. It wound up around the stalks of the sorghum. In addition to a sorghum field, and sometimes on the edges of a sorghum field, pumpkin (pampuna, cucumber (konkomber) and watermelon (patia) were also grown. Peanuts were usually grown completely separately.

Even after slavery ended, a good harvest was super important because sorghum flour was the main food on Curaçao, especially in the neighborhoods outside the city. Until the 1960s, you could see green “kunuku’s” everywhere in Banda Bou from October to January, all full of sorghum. The sorghum harvest was always done with the help of neighbors, friends, and acquaintances. They’d cut off the sorghum panicles with a sharp knife and put them in a bag the harvester had with them. Each planter had a special day to harvest their sorghum. They’d play the “kachu,” the horn of a bull, while the women took care of the food. Usually, they’d also slaughter a goat and drink rum. After all the sorghum was harvested, they’d have the traditional harvest festival “Seú.” The Seú parade, which is still celebrated every year, is a direct cultural descendant of this harvest festival.

The sorghum panicles were kept in a special place called a “djogodó.” It was part of a kunuku house that didn’t have a door, but it had a small window. This way, mice and rats couldn’t get into the sorghum and eat it. Sometimes, they would crush the sorghum panicles in a wooden pestle called a “pilón.” This would loosen the sorghum seeds from the panicles.

Then, the corn was cleaned. This was done in two steps: “djadja” and “bencha”. At the djadja, the tapushi, which were the remains of the panicles, were carefully removed by hand. Then, the bencha began. This involved standing in the wind and pouring the corn kernels from a height of about a meter into another bucket. During this process, the “bagás,” which were the leftovers of the husks of the corn kernels, were carried away by the wind. It was important to be careful, as if the “bagás” landed on the skin, they could cause quite a bit of itching. After that, the sorghum was ready to be ground.

Back in the 1950s and even the 60s, there were wind-powered sorghum mills. It’s a shame that none of them are left. Later, there were machines that were powered by motors. On Banda Bou, this happened at the LVV post in Sta. Martha. People brought sorghum panicles there, and after some mechanical processing, they’d give them sorghum flour. People had to pay a small fee for this service.

After the sorghum panicles were cut off, the stems were cut almost to the ground. The cut stems were used as animal feed during the dry months. If it rained again after cutting down the sorghum, the plant would grow again. With good rainfall, one could then harvest a second time. But this didn’t happen often.

Sorghum is still grown here and there on Curaçao. One of the farmers, known as a “kunukero” in Papiamento, is Prins Doran from Dokterstuin. A photo of his recent harvest is attached. He explained that he currently sows the seeds directly into his field and then plows them in using a tractor with a plow attachment. See also the two video's by Prins Doran attached below.

Harvest maishi chikí

Photo credits: Prins Doran, Dokterstuin

This article delves into the fascinating world of sorghum cultivation. Sorghum was the star crop on the plantation, and its success was crucial for the owner’s financial well-being. In our next article, we’ll explore the economic implications, profitability, and financing of these plantations.

10. The Cultivation of Maishi Chikí (Sorghum) on the Curacao Plantation